|

|

|

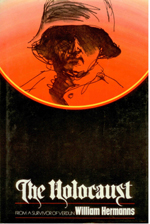

Click bars for Navigation ---- ---- Published Books by William Hermanns - Click cover image for it's webpage.  ---  Out of print books available - email us Translate page

---

Like our facebook page WilliamHermanns to get website update notices and some uploaded poetry that talks to your soul. --- Please help support this website. We'll continue to upload more gems from the archives. See Contact Page to communicate with us. To My NeighborSeelentränenNavigationContact / Kontakt |

||||

|

|

English PoetryClick on buttons below to navigate to the page. The Poetry and Song lists include those writings that have been uploaded to this website as well as the complete list of writings. ---- Click on buttons below for navigating to segments of his life on this page: ---- Passion and Compassion - Introduction to the First Book of English Poems of William HermannsAfter receiving a visa in 1937 to enter the United States with the help of sponsorship by his sister Hilda who had married an American citizen, William Hermanns began relying on English to also express his poetic muse. He published his first book of poetry in 1948 under the title Passion and Compassion. His introduction is reproduced below, as it demonstrates his passion and committment as a poet:  THE STORY OF THIS BOOK When Hitler became Reich Chancellor, a premonition of danger made me give up all that I possessed, pack what I could carry, and leave Germany in search of a new homeland. A few years later when the German armies set fire to Poland, I who had wandered over half the globe, was grateful that The United States of America had opened her doors to me, so that I might rest my weary feet, and for this, I desired to give something in return to her people who had accepted me as one of their own. But what could I, an alien and a pauvre diable, give to a country so vast, rich, and powerful as America? The answer was soon to come. One evening, I was thrown, purely by chance, into the midst of The Poetry Society of Boston. A young woman was asking each one in the audience to write a poem which, like "The Marseillaise" might become the herald of liberty against aggression. "America," she said, "has many songs, but not 'the song'. Perhaps one among you is he who will fulfill the need of this grave hour, for soon this country will be embroiled in the flames of war." How strange, I thought, that of all evenings and places in Cambridge and Boston, I should enter this very evening an ancient room of a gabled house on Beacon Hill and hear a young poetess speak of the kind of gift that I felt inspired to give to the American people. Perhaps is was as Alexander Pope once said: "All chance is direction not understood." I was determined to write a poem for the American people! Certainly destiny had equipped me to write a poem, and with the blood of my own past. Had I not heard the French soldiers sing while defending Verdun against the Kaiser's armies, "Allons enfants de la patrie?" Had I not seen the results of Nazism in the concentration camps? That evening I left The Poetry Society with a burning desire. Whether I had a poetical gift of one, five, or ten talents, I was determined to use whatever I possessed. Thus, "Free Men Go Forth" came into existence. Naturally, this poem did not spring from my head as did Pallas Athena, clad in splendid armor, from the head of Jupiter. It was the work of two years, for the sad pictures in my mind were still so real that each line written had to struggle for survival against a hundred other lines yearning for expression. I knew, moreover, what made my struggle more poignant; only a message purged from my own love and hate could become a lasting part of everyone's thought and make them say, "These thoughts are my thoughts, but never before did I realize it!" Having finished the poem I sent it to several composers, but each refused to set it to music. Thus, I was forced to compose the music myself. I invited a few Harvard students to my home and had them decide which of my three melodies they liked most. How enthusiastically they sang, and how my heart thrilled as I listened to their bases, baritones, and tenors! I called the anthem, "Song of the United Nations". Meanwhile, the flames of Warsaw had spread to Pearl Harbor. I sent the poem to the White House with a dedication to President Roosevelt and to Prime Minister Churchill, who was in Washington at that time. Both of them thanked me for the song. Even though they expressed the hope that the armed forces would receive my anthem, this hope proved to be a cloud without rain, passing over the parched land where poets dwell. The army newspaper, "Stars and Stripes", refused to publish it; for at that time, although attached to The War Department in Washington, I was not in a fighting unit. Then hope came from the headquarters of The War Bond Drive Committee. I was told that this song would bring millions to the Treasury Department, for Lily Pons and Lauritz Melchior and others would sing it from coast to coast. One thing, however, had to be done first. The song had to be printed and copyrighted, which was out of the province of the committee. I travelled to New York and offered it to a well-known publisher. He said, "Your poem is excellent, but in view of the paper shortage, I can only consider people who me known." Another publisher said, "Your poem is excellent, but we have our own composers. Since you have no 'name', I advise you to renounce your melody and have them write a new one. Then I will print it and offer it to The War Bond Committee. Of course, you will have to pay all the expenses !" I explained that I had written this song without money and without price for the cause of freedom, and could not understand why a poor immigrant, like myself, should pay five hundred dollars, or more, for printing expenses, while The War Bond Committee might make thousands of dollars from it. The publisher did not make any concessions. I left! Sometime later I heard a radio choir in New York which included each week a new or unknown song to the armed forces on their program. I sent a registered letter to the soloist enclosing the song as a gift - it came back unopened. I then dispatched the letter to my sister, who lived near New York City, requesting her to show this letter to the soloist and to explain my motives for writing the song. My sister returned the song with the woeful description of her failure in a letter. Having been announced to the lady after the program, she had no chance to approach her because of the gathered throng. My sister then posted herself before the star's dressing room. When she appeared, still followed by her admirers, my sister extended the letter with some words of explanation, but was brushed aside by the lady with the remark that she had no time, and that the song should be sent to the director of the choir. Should I re-address this song to New York? Going to the same office, it might land on the other side of the desk. I would not. Meanwhile, the war had ended. The young poetess from Boston who had inspired this song notified me that the president of a college in South Carolina was seeking war poems for an anthology. I sent "Free Men Go Forth", but never received an answer. Perhaps there was something wrong with "Free Men Go Forth” - perhaps with all my poems? I took several of them to a woman having the degree of Doctor of Literature to find out. She rejected them, saying that the time for rhymed poems had passed. She advised me to study the technique of free verse, praised Gertrude Stein, and prophesied that within the next fifty years Shelly would be forgotten. After this answer, should I bury my talent? I tried another critic, the distinguished poet, Robinson Jeffers. He said "Free Men Go Forth" as well as "Dunkirk", was Byronian; that all of my poems were un-American; and that no one would read them. He added this, however, "Your poems betray a deep feeling, and appeal more to the emotion of the reader than most poems published today." What now? Should I still bury my talent? At that time, a radio program, "Hello England, Hello America", asked each Sunday for letters of interest to both nations, which would be read over the radio. I sent my song with its story and listened Sunday after Sunday. Letters were read in which a scout described scout life, asking whether American scouts had a cub movement; or in which an Englishwoman wished to know about mountain-climbing in America. Letters were read from America to England, asking whether an old house in Bristol was still standing, or whether the English were still beef-eaters. But my letter, containing an unknown poem dedicated to Churchill and Roosevelt, was not read. I asked myself, why was I so persistent? It was, I believe, that the poem had become to me as a child to its mother. When a child is young, it steps in the lap of its mother; when it grows up it steps on her heart. My love for the poem increased with every disappointment. One day I read that Queen Mary would soon celebrate her eightieth birthday, and The British Broadcasting System had asked her to "command" a program for that day. "Her Majesty", went on the paper, "would probably choose a mystery story and a program made up of comedians and singers." This announcement caused my thought to slip into the past. I remembered that I had once been a guest in a Berlin palace, and that the wife of the last Kaiser had become interested in my poetry, which was written in German. She said once that she kept my poems in a special album. Could it be that the Queen would also appreciate my poetry? I said to myself, "She need only lift her little finger and my poems will be published." I sent her "Free Men Go Forth", "Dunkirk" , "The Women of London" and "England", as a birthday gift, with a letter in which I expressed the hope that these unpublished poems might be made known to the English people, who with the Americans, fought together for victory. An answer came in a crowned envelope, - had she read my poems - would she lift her finger? I opened it after seating myself in a comfortable choir before the fireplace. The letter contained a few lines in large type saying: "The private secretary to Queen Mary is instructed to thank Mr. William Hermanns for his expression of good wishes for the anniversary of her birthday, and to say that Her Majesty has much pleasure in accepting the copies of his unpublished verses." In the meantime her birthday had been celebrated over the radio by a program for which a well-known writer had been commanded to compose a mystery story, and famous comedians and singers to give a performance. Yet, could all the orations of praise ever given to England outshine these four poems? The lips which uttered those lines for Britain's glory had not been shaped by the self-assurance of a' dignitary but by the heartfelt thanks of a refugee who had bowed down to kiss the soil of England; who aging and aching, had to learn England's language like a child, in order to express what he thought. Watching the flames eat their way through the logs in my fireplace, my thoughts wandered from this letter to a great and humble man, who as a petitioner, lingered often in the ante-room of a palace of a mighty English lord. His lordship only remembered this petitioner when he no longer needed to be remembered, for his life of sorrows was almost spent, and he had become famous! With Samuel Johnson was fulfilled the words of Isaiah: "And kings shall be thy nursing fathers, and their queens thy nursing mothers. They shall bow down to thee with their face toward the earth, and lick up the dust of thy feet, and thou shalt know I am the Lord, for they shall not be ashamed that wait for me." I shall not be ashamed. I now saw clearly that each one of us is given a talent; to use it is to express oneself, not to frustrate oneself. Talent is like an acorn; its germ is in the seed, not in its environment. A fool is he who digs in the graveyard of human opinions! Whether I write like Byron or like Gertrude Stein has little bearing on my talent, and I said to myself: "I will no longer strive for happiness, but just be happy; I will no longer look for a patron, but I will be patron for the angels in heaven." Thus I pondered by the fireplace, and suddenly I seemed to hear a voice in the room: "Do you know I still sing your song 'Free Men Go Forth' while soaring in my plane over Italy and Germany?" The stalwart pilot wearing wings on his breast, who once spoke these words to me, now took shape above the glowing embers. He had not come alone. Other men, all familiar to me, grew into my vision. Yes, they had come again, the bases, the baritones, the tenors, and grouped themselves around the piano to sing once more "Free Men Go Forth". All wore uniforms-there were three among them whose eyes could no longer see. Although the wood in my fireplace had long been consumed, a comfort and a warmth spread through the room, I became unspeakably happy. I took the poem and the three melodies I had written and placed them on the smoldering ashes. How good to see them burn! The world did not owe me anything. My toil of years had been richly rewarded by the soldier-students of Harvard. A few months ago, a young woman in Los Gatos, California, wished me to recite some of my poems. She asked my permission to write one of them down. The one she chose was "Free Men Go Forth". Fourteen days later she showed me the poem in print and asked for some more poems, revealing herself as a printer at a newspaper office. I gazed at my poem with amazement. There in print, it seemed to have become grown-up, looking away from me into the world. If now, this poem and others of mine can at last be read it is thanks to Freda, that little woman who stands in coveralls before the printing press. William Hermanns Los Gatos, California, 1948 The first poem in Passion and Compassion is

Poems:

P031 Poems

Poems are the voice of one Crying in the wilderness, Moving barriers of damnation, Freeing those who are bound. Put your bridal garments on, Take his love filled cup to bless Man and tree of his creation - You are on holy ground. William Hermanns [P031] ----

|

Please support

our sponsors. Click on image to be directed to their website ~~~~~~~~  ~~~~~~~~  ~~~~~~~~  ~~~~~~~~ Norton & Holtz Business Solutions  ~~~~~~~~  ~~~~~~~~  ~~~~~~~~ Published Books below: Click cover image for it's webpage:  Available at Amazon. For Hardbacks Contact us. ---  Inquire on out of print books ~~~~~~~~ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

Prose and Plays |

|

Poetry |

|

Events |

|

Website Info |

Website © Copyright 2011-2022 by Kenneth E. Norton Articles by William Hermanns (c) by William Hermanns Trust |

||||||